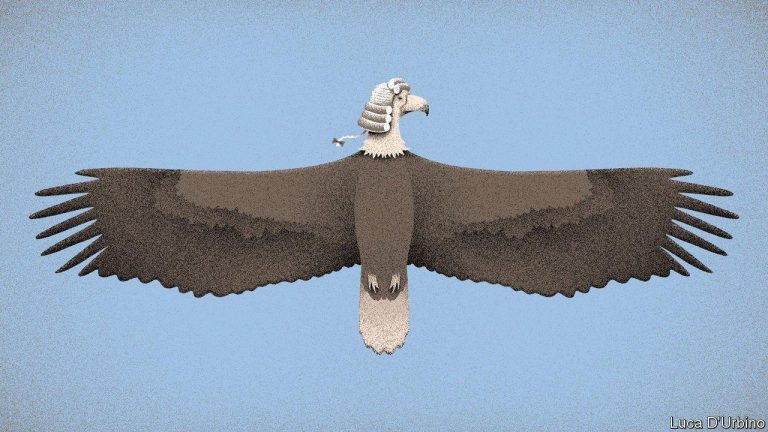

- Bribes and gratuities to state and local government officials are not subject to the federal anti-corruption statute.

- “Bribes” are “payments made or agreed to before an official act” to influence the official to carry out “that future official act.” By contrast, “gratuities” are payments made “after an official act,” “with no agreement beforehand,” and “are not the same as bribes before the official act.”

Yes, you read that right.

- Pre-action inducements are worse than post-action rewards.

- The legality of a quid pro quo is determined in part by whether it (a) purchases an outcome or merely (b) rewards an outcome after the fact.

Justice Kavanaugh, writing for the majority, likened acceptable gratuities to treating a favored teacher to Chipotle at the end of the school year. (Incredibly, the highest court in the land is expressly preoccupied with ensnaring millions of citizens over burritos.)

While this may all sound benign, or indeed, absurd, the dissenting justices argued that this position opens the door for public positions to be used and exploited for private gain. Oh, and that burritos would not ever reasonably be considered an illegal bribe…unless, perhaps, you added guacamole.

(OK, they didn’t actually say the part about guacamole.)

How did this all start? Enter James Snyder, a former Indiana city mayor. While he was in office, the city awarded two contracts worth around US$1.1 million to a garbage truck company. Less than a year later, the company handed Snyder a US$13,000 check. Snyder claimed this was for his consulting services, but the FBI and federal prosecutors called it an illegal reward for rigging the contract process.

How does this involve federal law? Section 666 in a nutshell:

- Criminalizes embezzlement, theft, fraud, or corrupt actions involving property valued at $5,000 or more.

- Targets anyone who corruptly accepts or offers anything of value to influence or reward public officials.

- Imposes fines, prison time of up to ten years, or both.

Snyder was federally convicted of accepting illegal bribes, a conviction upheld by a federal appeals court. During the appeal, Snyder argued that the federal statute criminalized only “bribes” and not “after-the-fact gratuities,” prompting the Supreme Court to step into the fray. The majority agreed with Snyder, ruling (among other things) that determining the legality of after-the-fact payments demands more nuance than straightforward bribes.

This ruling comes at an interesting time, with the Supreme Court recently adopting its first ever ethics code amid revelations about justices and their families receiving luxury travel and gifts from donors. Further, critics argue that this decision impedes the federal government’s ability to combat corruption: to avoid prosecution, simply delay the quid pro quo until after the official act is done.

The decision marks a significant shift in anti-bribery and corruption laws. While the aim was presumably to provide clarity, the ruling has also sparked widespread concern about its implications for combating corruption effectively. Time will tell whether it emboldens corrupt officials. Stay tuned!

We are a boutique law firm specializing in anti-bribery compliance. Need advice on how to create (or refine) your compliance program? Call us today!